The new era of management for progressive, complex, genetic conditions, such as mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) disorders, hinges on the efficient coordination of each patient’s healthcare team by a coordinated, multidisciplinary care-delivery model.1

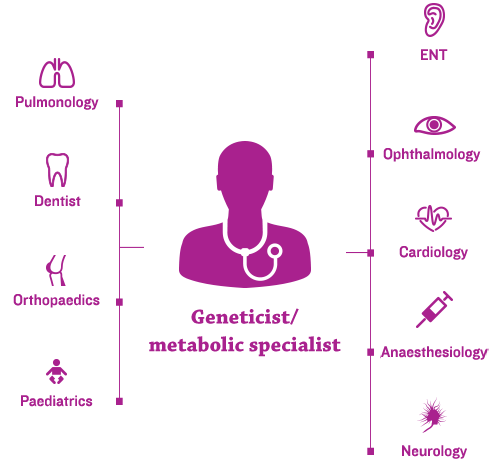

Geneticists and/or metabolic specialists are typically at the centre of the coordinated, multidisciplinary care-delivery model and an individualised management plan.2,3

Given that ENT manifestations are common in MPS – and often appear early in the disease course – the ENT specialist plays an essential role in the multidisciplinary medical team.4,5

Many MPS disorders have available management guidelines and specialty-specific consensus recommendations regarding lifelong management of MPS. Guidelines typically recommend the following3,7:

Because ENT symptoms often manifest at an early age, the otolaryngologist is in a prime position to initiate diagnosis and refer for confirmation with genetic testing.5 Early and ongoing assessments from a coordinated care team can improve patient outcomes and may help prevent irreversible damage.7

Due to glycosaminoglycan buildup in the ear, patients with MPS have an increased risk of otitis media with effusion and acute otitis media.5,8 Management considerations include the following:

Upper airway obstruction in patients with MPS can range from varying degrees of sleep apnoea to life-threatening airway emergencies. Management strategies for airway obstruction include the following5:

It is important to note that while ENT manifestations and complications are almost universal across MPS types, specific signs and symptoms can differ across and within MPS disorders.5 Individualised management plans should be tailored to specific needs, depending on presenting symptoms and MPS type.

A summary of general and ENT features of MPS syndromes can be found below.

Adapted from Yueng, Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2009.

Frequency of assessments and involvement of specific specialists vary across the different MPS types. For patients with MPS diseases associated with primary neurodegenerative and cognitive complications, such as MPS I, II and III, additional and regular neurobehavioural and psychiatric evaluations are recommended.7,12,13

In addition to specialty-specific assessments that should be done to facilitate positive long-term outcomes for patients with MPS, important steps can be taken by the coordinating doctor, typically the geneticist and/or metabolic specialist, related to general health. Their role in educating other healthcare professionals (e.g. dentists, physiotherapists, paediatricians, family doctors) and families about the disease and general management strategies is critical and should include the following1:

Specialty-specific assessments, as well as regular physical examinations and overall health interventions, should follow recommended guidelines, which may vary among MPS subtypes.3

Improvements in the treatment of MPS disorders are contributing to long-term outcomes for patients, necessitating new approaches to lifelong management.

As patients age, some may begin to manage their own healthcare, making doctor-guided transition to the adult setting critical.3 Doctors should ensure the following:

The transition from paediatric to adult care and long-term adult care are critical areas to address in care plans for adolescent and adult patients.3 Long-term care considerations are ideally best addressed in a centre with significant MPS experience, and they require careful coordination across specialties.3,15 Long-term issues include but are not limited to the following:

Long-term management of MPS disorders – including ongoing assessments and a site-specific transition strategy from paediatric to adult care – may lead to sustained improvement in quality of life and a better future for your patients.3,15-17

References: 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Defining the PCMH. https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh. Accessed December 15, 2015. 2. Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses: a heterogeneous group of disorders with variable pediatric presentations. J Pediatr. 2004;144(suppl 5):S27-S34. 3. Hendriksz CJ, Berger KI, Giugliani R, et al. International guidelines for the management and treatment of Morquio A syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2014;9999A:1-15. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36833. 4. Mesolella M, Cimmino M, Cantone E, et al. Management of otolaryngological manifestations in mucopolysaccharidoses: our experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2013;33(4):267-272. 5. Wold SM, Derkay CS, Darrow DH, Proud V. Role of the pediatric otolaryngologist in diagnosis and management of children with mucopolysaccharidoses. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(1):27-31. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.09.042. 6. Spinello CM, Novello LM, Pitino S, et al. Anesthetic management in mucopolysaccharidoses. ISRN Anesthesiol. 2013;2013:1-10. doi:10.1155/2013/791983. 7. Muenzer J, Wraith JE, Clarke LA, International Consensus Panel on the Management and Treatment of Mucopolysaccharidosis I. Mucopolysaccharidosis I: management and treatment guidelines. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):19-29. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0416. 8. Simmons MA, Bruce IA, Penney S, Wraith E, Rothera MP. Otorhinolaryngological manifestations of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(5):589-595. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.01.017. 9. Motamed M, Thorne S, Narula A. Treatment of otitis media with effusion in children with mucopolysaccharidoses. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;53(2):121-124. 10. Yeung AH, Cowan MJ, Horn B, Rosbe KW. Airway management in children with mucopolysaccharidoses. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135(1):73-79. doi:10.1001/archoto.2008.515. 11. Hendriksz CJ, Harmatz P, Beck M, et al. Review of clinical presentation and diagnosis of mucopolysaccharidosis IVA. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110:54-64. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.04.002. 12. Neufeld EF, Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, eds. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. Vol 3. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002:2465-2494. 13. Scarpa M, Almassy Z, Beck M, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type II: European recommendations for the diagnosis and multidisciplinary management of a rare disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:72. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-72. 14. James A, Hendriksz CJ, Addison O. The oral health needs of children, adolescents and young adults affected by a mucopolysaccharide disorder. JIMD Rep. 2012;2:51-58. doi:10.1007/8904_2011_46. 15. Coutinho MF, Lacerda L, Alves S. Glycosaminoglycan storage disorders: a review. Biochem Res Int. 2012;2012:471325. doi:10.1155/2012/471325. 16. Kakkis ED, Neufeld EF. The mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Berg BO, ed. Principles of Child Neurology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1996:1141-1166. 17. Lehman TJA, Miller N, Norquist B, Underhill L, Keutzer J. Diagnosis of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology. 2011;50(suppl 5):v41-v48.